Reformed scholastics - 16th and

17th centuries

We propose to publish studies and reviews of classical Reformed political theories, and on the introduction of revisionist theories that led to the modern view of the church as a voluntary association or assembly of the elect, and on the original Reformed bicovenantal theology in distinction to the monocovenantal and tricovenantal views that predominate today. When the Reformed view of culture is mentioned, what almost always comes to mind is Kuyperian transformationalist philosophy. The true Reformed cultural view remains largely unknown. Today, the Kuyperian intellectual hegemony is being challenged, and it is important to explain how historical Reformed thought differs from it. The Reformed began to develop an integral theology in which God's program since the Fall was integrated into the unifying Covenant of Grace. If this was the center of God's action, how did the state and general cultural endeavors fit into this covenant? At this point, the Reformed drew on the medieval heritage of various scholastic authors to propose a theory of what the state was. This dovetailed with what Paul was saying about the magistrate's purpose to do good. It was possible to relate this activity to the Covenant of Grace, since the State was considered a partner of the institutional Church. As formulated in the Reformed confessions, the state was responsible for maintaining the establishment of the church with correct doctrine, and the state made sure that the people submitted to this church. In this way, the church could carry out its task not only without hindrance, but with the full support of society. The Enlightenment destroyed the intellectual religious consensus in the peoples of Europe and resulted in a growing unwillingness to support the establishment of a traditional doctrine. In the Netherlands there was the additional problem that the presence of many Roman Catholics and Arminians, as well as Reformed, meant that the actual ecclesiastical establishment had never been able to conform to theory. At the same time, however, the Reformed were strong enough to consider themselves capable of aspiring to a comprehensive program for society. This unique situation led to the invention of a substitute program for the scholastic one that was considered to have failed. In New England, where one might suppose that Puritan control would have led to a new cultural program, the rejection of the Reformed idea of the Church in favor of a pure Church of true believers set in motion a sequence of changes that led not only to a loss of control, but eventually to a conception of the Church as an association separate from society. The solution found in the Netherlands, which has adopted the names Kuyperianism, transformationalism or neo-Calvinism, was a radical alternation of Reformed theology, introduced mainly by Abraham Kuyper. Where there had been a bi-covenantal theology, the Covenant of Works at the time of creation and God's restorative program of the Covenant of Grace, a third covenant, the Common Covenant, was introduced. While most of traditional Reformed theology was to remain bound to the two traditional covenants and, it was thought, to remain unchanged in its own sphere, cultural issues, i.e., state, society, economy, etc., were to be based on the Common Covenant. This could be seen as a second program of God distinct from that of the Covenant of Grace, and it would no longer be necessary to integrate everything somehow into the Covenant of Grace in order to give everything a Christian meaning. Since, however, this Common Covenant was thought to be under God and to be a covenant, a theological principle, but its own, had to be proposed as a kind of index of the functioning of this covenant. This principle was Common Grace. But the principle had to be balanced by a dialectical opposite, so there was a divisive principle, Antithesis, placed beside the unifying one of Common Grace. Around this was built a conceptual system based largely on the concepts of German theosophy, which had become popular among some Dutch Reformed theologians. Antithesis was, in fact, one of these concepts. Although the intention of this philosophy was to introduce a Christian transformative cultural vision, capable of advancing on its own legs independently of theology, the most fundamental choice that made this possible was the separation of culture from the Covenant of Grace, giving it its own distinct covenantal basis. This meant that the program could also be inverted. Once culture was separated from the Covenant of Grace, an anti- transformational cultural theory could also be constructed that discounted the importance of culture, since culture was now seen as unrelated to the Covenant of Grace. This, in fact, happened, and it came about in this way: Since Common Grace had to operate under a divine covenant, it was inevitably treated as a kind of theological principle, and as such could not really stand outside the Covenant of Grace. Common Grace provided a way to introduce Arminian tendencies into Reformed Theology without having to base them on Arminian principles that the Confessions had condemned. This proved irresistible to those theologians who wished to modify their ideas about salvation. Thus, Kuyperianism entered Presbyterianiam when several Dutch Reformed theologians settled in Westminster Seminary. Cornelius Van Til especially wished to make theological use of Common Grace, and he also accepted the tricovenantal scheme. But for Van Til, the Common Covenant was a limiting notion that circumscribed the scope of application of the Covenant of Grace. He did not seem to have much enthusiasm for the transforming character of Christianity. However, some of his disciples, notably R. J. Rushdoony, were very much oriented toward a transformational vision, but to realize it they had to go beyond Kuyper and add a broad biblical basis to their transformationalism. At the same time, the opposite, anti-transformational, view developed at Westminster. Meredith Kline saw the Common Covenant as necessary only to keep the world functioning long enough for God's program under the Covenant of Grace to be carried through to completion. At that time, everything that had developed under the Common Covenant would be consigned to destruction in a conflagration at the end of the world, and would be replaced by a heavenly order pertaining to the other covenants. Kline's theology was developed by his successors as the Radical Two-Kingdom theology. As anti-transformationalists, the R2K consider themselves anti- Kuyperian, although they rely on Kuyper's tricovenantalism as much as the transformationalists do. For them, the Common Covenant serves to set aside culture as foreign to God's program. Both transformationalists and Radical Two-Kingdom theologians want to claim a Reformed identity, perhaps primarily to control seminaries and denominations, and so they have engaged in falsifying the theology of Calvin and the other Reformers to try to erase the scholastic view of the relationship of culture to the Covenant of Grace. At the same time, a third group, disillusioned Kuyperians who have renounced the tricovenantal scheme, formulated monocovenantal theologies in which grace and works are combined in a single covenant. Some of them have applied a strong leveling tendency to history, adopting a strongly clerical view of the Church, and even projecting priesthood and sacrifice back to before the fall, in order to make the operation of the one covenant more uniform in all periods. They also have endeavored to misrepresent the theology of the Reformers.Early view of covenants and society

- Pufendorf On Civil Religion and the Church as a Mere Association Ruben Alvarado - - Fountainhead of Liberalism (Review of Fountainhead of Federalism by Charles S. McCoy and J. Wayne Baker The contrast of the original Reformed view with Baptist and modern Reformed views of the covenant A Comparison of Baptist and Reformed Views of the Covenants, Review of Pascal Denault, The Distinctiveness of Baptist Covenant Theology: A Comparison Between Seventeenth- Century Particular Baptist and Paedobaptist Federalism Difference between modern and scholastic Reformed theologies Fake Theology: Radical Two-Kingdom Theory, a prehistory and a review of Saved to be Warriors: Exposing the Errors of Radical Two-Kingdom Theology, by Bret McAtee

Contra Mundum

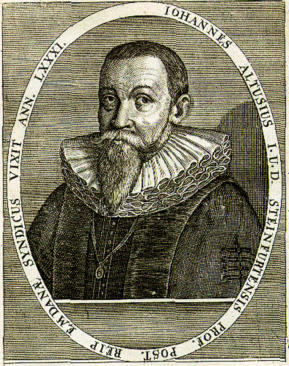

Johannes Althusius

William Ames

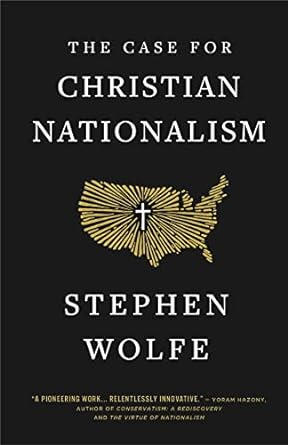

Wolfe’s view of politics draws on the political

principles of the Reformed Scholastics. Ironically, his

view is condemned by the promoters of the inverted

Kuyerianism of the Radical Two-Kingdom theology,

who claim to have returned to a Thomist

scholasticism to support their idea of a religiously

neutral political order.

A mainly Thomist group published an attack on

Vantillian presuppositional under the title of

Without Excuse. In Divided Knowledge the

many misrepresentations of Van Til, Bahnsen,

and Frame’s views are analyzed, but also the

failure of these views are pointed out.

Along with this there is is a analysis of the

dogmatism, ignorance and misrepretation of

this history of philosophy, that charactarized

this neo-thomist retropapist movement.

Exercitation qui dolor dolor lorem proident commodo nisi.

© Lorem ipsum dolor sit Nulla in mollit pariatur in, est ut dolor eu

eiusmod lorem

Reformed

scholastics -

16th and 17th

centuries

We propose to publish studies and reviews of classical Reformed political theories, and on the introduction of revisionist theories that led to the modern view of the church as a voluntary association or assembly of the elect, and on the original Reformed bicovenantal theology in distinction to the monocovenantal and tricovenantal views that predominate today. When the Reformed view of culture is mentioned, what almost always comes to mind is Kuyperian transformationalist philosophy. The true Reformed cultural view remains largely unknown. Today, the Kuyperian intellectual hegemony is being challenged, and it is important to explain how historical Reformed thought differs from it. The Reformed began to develop an integral theology in which God's program since the Fall was integrated into the unifying Covenant of Grace. If this was the center of God's action, how did the state and general cultural endeavors fit into this covenant? At this point, the Reformed drew on the medieval heritage of various scholastic authors to propose a theory of what the state was. This dovetailed with what Paul was saying about the magistrate's purpose to do good. It was possible to relate this activity to the Covenant of Grace, since the State was considered a partner of the institutional Church. As formulated in the Reformed confessions, the state was responsible for maintaining the establishment of the church with correct doctrine, and the state made sure that the people submitted to this church. In this way, the church could carry out its task not only without hindrance, but with the full support of society. The Enlightenment destroyed the intellectual religious consensus in the peoples of Europe and resulted in a growing unwillingness to support the establishment of a traditional doctrine. In the Netherlands there was the additional problem that the presence of many Roman Catholics and Arminians, as well as Reformed, meant that the actual ecclesiastical establishment had never been able to conform to theory. At the same time, however, the Reformed were strong enough to consider themselves capable of aspiring to a comprehensive program for society. This unique situation led to the invention of a substitute program for the scholastic one that was considered to have failed. In New England, where one might suppose that Puritan control would have led to a new cultural program, the rejection of the Reformed idea of the Church in favor of a pure Church of true believers set in motion a sequence of changes that led not only to a loss of control, but eventually to a conception of the Church as an association separate from society. The solution found in the Netherlands, which has adopted the names Kuyperianism, transformationalism or neo- Calvinism, was a radical alternation of Reformed theology, introduced mainly by Abraham Kuyper. Where there had been a bi- covenantal theology, the Covenant of Works at the time of creation and God's restorative program of the Covenant of Grace, a third covenant, the Common Covenant, was introduced. While most of traditional Reformed theology was to remain bound to the two traditional covenants and, it was thought, to remain unchanged in its own sphere, cultural issues, i.e., state, society, economy, etc., were to be based on the Common Covenant. This could be seen as a second program of God distinct from that of the Covenant of Grace, and it would no longer be necessary to integrate everything somehow into the Covenant of Grace in order to give everything a Christian meaning. Since, however, this Common Covenant was thought to be under God and to be a covenant, a theological principle, but its own, had to be proposed as a kind of index of the functioning of this covenant. This principle was Common Grace. But the principle had to be balanced by a dialectical opposite, so there was a divisive principle, Antithesis, placed beside the unifying one of Common Grace. Around this was built a conceptual system based largely on the concepts of German theosophy, which had become popular among some Dutch Reformed theologians. Antithesis was, in fact, one of these concepts. Although the intention of this philosophy was to introduce a Christian transformative cultural vision, capable of advancing on its own legs independently of theology, the most fundamental choice that made this possible was the separation of culture from the Covenant of Grace, giving it its own distinct covenantal basis. This meant that the program could also be inverted. Once culture was separated from the Covenant of Grace, an anti- transformational cultural theory could also be constructed that discounted the importance of culture, since culture was now seen as unrelated to the Covenant of Grace. This, in fact, happened, and it came about in this way: Since Common Grace had to operate under a divine covenant, it was inevitably treated as a kind of theological principle, and as such could not really stand outside the Covenant of Grace. Common Grace provided a way to introduce Arminian tendencies into Reformed Theology without having to base them on Arminian principles that the Confessions had condemned. This proved irresistible to those theologians who wished to modify their ideas about salvation. Thus, Kuyperianism entered Presbyterianiam when several Dutch Reformed theologians settled in Westminster Seminary. Cornelius Van Til especially wished to make theological use of Common Grace, and he also accepted the tricovenantal scheme. But for Van Til, the Common Covenant was a limiting notion that circumscribed the scope of application of the Covenant of Grace. He did not seem to have much enthusiasm for the transforming character of Christianity. However, some of his disciples, notably R. J. Rushdoony, were very much oriented toward a transformational vision, but to realize it they had to go beyond Kuyper and add a broad biblical basis to their transformationalism. At the same time, the opposite, anti- transformational, view developed at Westminster. Meredith Kline saw the Common Covenant as necessary only to keep the world functioning long enough for God's program under the Covenant of Grace to be carried through to completion. At that time, everything that had developed under the Common Covenant would be consigned to destruction in a conflagration at the end of the world, and would be replaced by a heavenly order pertaining to the other covenants. Kline's theology was developed by his successors as the Radical Two- Kingdom theology. As anti- transformationalists, the R2K consider themselves anti- Kuyperian, although they rely on Kuyper's tricovenantalism as much as the transformationalists do. For them, the Common Covenant serves to set aside culture as foreign to God's program. Both transformationalists and Radical Two-Kingdom theologians want to claim a Reformed identity, perhaps primarily to control seminaries and denominations, and so they have engaged in falsifying the theology of Calvin and the other Reformers to try to erase the scholastic view of the relationship of culture to the Covenant of Grace. At the same time, a third group, disillusioned Kuyperians who have renounced the tricovenantal scheme, formulated monocovenantal theologies in which grace and works are combined in a single covenant. Some of them have applied a strong leveling tendency to history, adopting a strongly clerical view of the Church, and even projecting priesthood and sacrifice back to before the fall, in order to make the operation of the one covenant more uniform in all periods. They also have endeavored to misrepresent the theology of the Reformers.Early view of

covenants and society

- Pufendorf On Civil Religion and the Church as a Mere Association Ruben Alvarado - - Fountainhead of Liberalism (Review of Fountainhead of Federalism by Charles S. McCoy and J. Wayne Baker The contrast of the original Reformed view with Baptist and modern Reformed views of the covenant A Comparison of Baptist and Reformed Views of the Covenants, Review of Pascal Denault, The Distinctiveness of Baptist Covenant Theology: A Comparison Between Seventeenth-Century Particular Baptist and Paedobaptist Federalism Difference between modern and scholastic Reformed theologies Fake Theology: Radical Two-Kingdom Theory, a prehistory and a review of Saved to be Warriors: Exposing the Errors of Radical Two-Kingdom Theology, by Bret McAtee

MyWebsite.com

- Home

- About

- subjects

- French

- Temas

- Auteresindice

- Autores-org

- Autores-a

- Autores-b2

- Autores-ij

- Autores-d

- Autores-ef

- Autores-g

- Autores-h1

- Autores-c

- Autores-k

- Autores-l

- Autores-m1

- Autores-no

- Autores-pq

- Autores-r1

- Autores-r2

- Autores-b1

- Autores-h2

- Autores-s1

- Autores-s2

- Autores-t

- Autores-uv

- Autores-w1

- Documentos

- Perspectivas

- Eng-biblical

- Eng-law

- Eng-law-reviews

- Eng-education

- Eng-arts

- Eng-history

- Eng-economics

- Eng-biography

- Eng-brown

- Spa-recon

- Spa-anglicanos

- Spa-arte

- Spa-cosmovision

- Spa-iglesia

- Spa-pacto

- Spa-refeurop

- eng-federalism

- Spa-economia

- Spa-posreformados

- Spa-milenio

- eng-collections

- spa-etica

- spa-comun

- spa-epistemologia

- spa-t-historia

- blog

- spa-educacion

- spa-politica

- spa-filosofia

- portugues

- spa-reino

- spa-escolasticos

- eng-scolastics

- spa-neocalvinismo

- eng-neocalvinism

- espanol-libros

- sobre